Luigi Galvani

|

Luigi Galvani was born in Bologna on 9 September 1737 from Domenico, a goldsmith, and Barbara Foschi. Around 1755 he entered the Faculty of Arts of the University of Bologna, where he studied with some followers of Marcello Malpighi’s rational approach to medicine. In 1759 he received doctorates in both medicine and philosophy, and three years later he became lecturer of surgery at the same University. In 1766 he was appointed professor of anatomy both at the University and at the Institute of Sciences of Bologna, at that time one of the leading scientific institutions in Italy. |

|

|

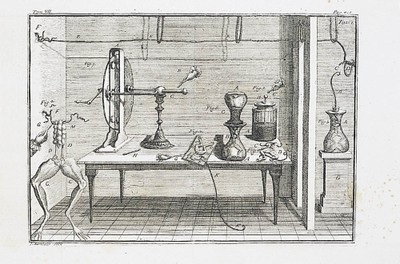

Galvani’s early investigations were on the anatomy of kidney and ear, but from ca. 1770 he focussed his interest on muscular motion, a topic highly debated in the Bologna scientific milieu. In the 1750s several members of the Institute of Sciences, including some of Galvani’s teachers, had indeed been involved in the discussion of Albrecht von Haller’s theory of “irritability”. For Haller, muscle contraction depended on an intrinsic property of muscular fiber, i.e. irritability, and not on the action of nerves, as previously thought. In order to test Haller’s theory, the Bologna scholars experimented mainly on frogs and introduced the use of electricity as the most efficient stimulus to produce muscle contractions, two aspects that would later characterize Galvani’s scientific practice. During the following two decades Haller’s theory won increasing approval, but the old theory of nerve action was not put entirely aside. In fact, the idea that animal motion was due to a nervous fluid that acted on muscles gained new strength thanks to the investigation on the effects of electricity on living organisms. These developments formed the background of Galvani’s own research on muscular motion. After some studies of irritability and heart motion, around 1780 Galvani began a systematic investigation on the action of electricity on frog nerves and muscles. In his home laboratory Galvani developed an original experimental practice that combined approaches derived from the study of electricity and from anatomo-physiological research (especially of Hallerian type, i.e. through stimulus-response experiments). The most important outcome of this practice was the discovery that muscle contraction could be produced by connecting nerve and muscle of a frog’s limb through a metallic arc. For Galvani, the muscle fiber was analogous to a Leyden jar (the first electrical capacitor) that contained electricity in an unbalanced condition. The contraction was the result of the electrical discharge of the muscle through the attached nerve due to a physiological (or experimental) stimulus. Galvani’s theory of animal electricity, published in 1791 in the De viribus elecricitatis in motu musculari, produced such a sensation that it was later compared to the French revolution. Among those who took an immediate interest in the new topic (soon renamed “Galvanism”) there was Alessandro Volta, who became the protagonist of a lively and engaging controversy with Galvani and his followers. The controversy, which catalysed science in the 1790s, proved to be a fundamental event for the science to come, as it prompted new capital experiments in the history of electrophysiology and fostered the invention of the battery, realized by Volta in 1800.

Further Readings: Medicine and science in the life of Luigi Galvani Exploring Galvani’s room for experiments

|

|